8bit-sized #1 | GenServer handle_call without a reply

This is the first issue of the series of blog posts that I introduced in my Recapping 2022 and a look into 2023 post. To save you from reading the whole thing if you haven’t done it yet, an 8bit-sized post is just a smaller type of post to share interesting findings, and distinguish them from the longer ones I sometimes write, and because 8bits = 1byte 🤓

Now, diving into what matters… You may have encountered a situation where you have a GenServer serving as a “Proxy” for another Process/External Application. If we’re interacting with an HTTP API, for example, we can easily obtain a synchronous response. Imagine an Actor that interacts with a GenServer.call function, and then it interacts with an external HTTP API, it’s possible to do {:reply, response, state} at the end of the respective handle_call. Now, imagine the situation where we are interacting with a different Process that will do some extra asynchronous processing, or we are communicating with an external App via sockets. Can you already spot the problem? In that case, it’s possible to assume we can’t use GenServer.call as it can’t obtain a response to reply to the caller. Well, that’s not entirely true, as we’ll see!

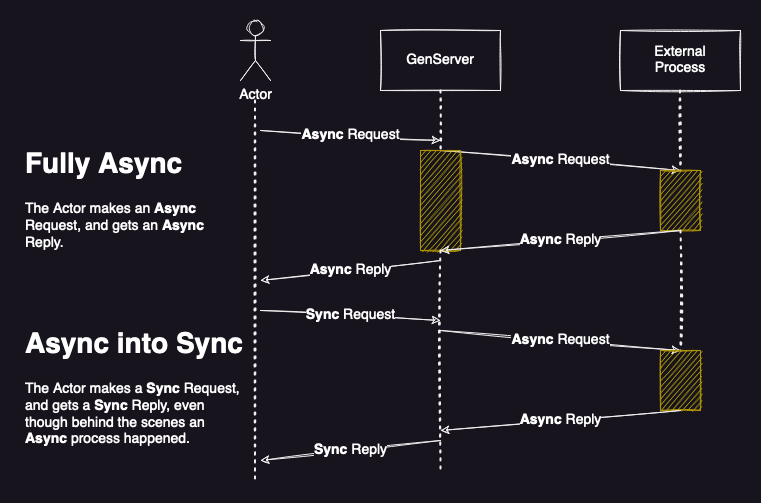

Looking at the scheme below, we have two different situations highlighted. In the first one, the Actor makes a request. This request is asynchronous, and the Actor knows about it, and it’s not worried about when a response will arrive. In the second situation, that Actor needs to make a synchronous request (either because of a better UX of the App, or some other technical constraint), but the external process is still doing the work asynchronously. The yellow blocks represent asynchronous waiting time, while the dashed line represents synchronous time.

To make this work, the GenServer request needs to be blocking as with a normal GenServer.call, but with one small change. As the title implies, we won’t reply! Let’s look at the code. I tried to mark the locations of the code with the order of execution (| N |) to help understand it better.

# a Client Function of a GenServer module

def synchronous_request(pid) do

send(pid, :perform_asynchronous_request) # |1| Client function to make a sync request

GenServer.call(pid, :wait_for_answer, 60_000) # |3| We make the call with no reply here!

# |6| This function returns in last

end

def handle_call(:wait_for_answer, from, state) do

new_state = Map.merge(state, %{from_pid: from})

{:noreply, new_state} # |4| Note that it doesn't :reply here. We just store who the caller was

end

def handle_info(:perform_asynchronous_request, state) do

ExternalProccess.make_asynchronous_request()

{:noreply, state} # |2| The Asynchronous Processing/Request is triggered

end

def handle_info({:asynchronous_request_response, res}, state) do

# This is where the GenServer will reply and unblock the process waiting

# for a response at GenServer.call(pid, :wait_for_answer, 60_000)

GenServer.reply(state.from_pid, res) # |5| We reply to the original caller we stored in the state

{:noreply, state}

end

# a barebone for an example External Process

defmodule ExternalProcess do

def make_asynchronous_request(caller) do

send(self(), {:process_async, caller})

end

def handle_info({:process_async, caller}, state) do

# Do some computation ...

send(self(), {:process_complete, result})

{:noreply, Map.merge(state, %{caller: caller})}

end

def handle_info({:process_complete, result}, state) do

send(state.caller, {:asynchronous_request_response, result})

{:noreply, state}

end

end

So, yeah, it’s pretty much this. No weird code laying around, just taking advantage of GenServer.reply/2. Check the documentation for reply/2 and handle_call/3 for the full perspective and if it works for your use case.

Things to take into account⌗

- Don’t forget that a

GenServeror any process in the BEAM can only handle 1 message at a time. This means that this approach can escalate into a problem really fast if you don’t evaluate your situation first. When I first discovered and used this, I knew for sure that the givenGenServerwas unique per user currently active in a specific part of the Web App (and that we’d never exceed the maximum number of running processes1). Also, each of theseGenServerswas expected to deal with new messages arriving at a fixed rate of ~4-7seconds, like a heartbeat, and any extra-ordinary load was most likely the result of a malicious user, that we could happily let clog his own (user) part of the system. - As pointed out by

derek-zhouin this ElixirForum reply, the example above only works if there can only be one unique client calling thisGenServer. If there are several clients, then you need to keep track of which request comes from, so replies don’t get misdirected, and clients are left hanging. - You also need to be careful with Timeouts and the possibility that the external App/Process can not answer on time!

- Don’t abuse this or

GenServersin general. Do you even need aGenServer? Here’s a great post with some insights on their dangers.

And that’s all for this first edition of my 8bit-sized posts. Hope you have liked it and, as always, see you in the next one 👋

Last time I checked, Erlang had a limit of simultaneously alive processes of 32768, by default. But this limit can be raised to at most 268435456 processes. More info here ↩︎